Centenarian Ray Stewart resides with his wife Eleanor at Bethany Cochrane’s assisted living facility.

His life is simple now, and quiet. They share a modest room with two windows and single beds facing each other.

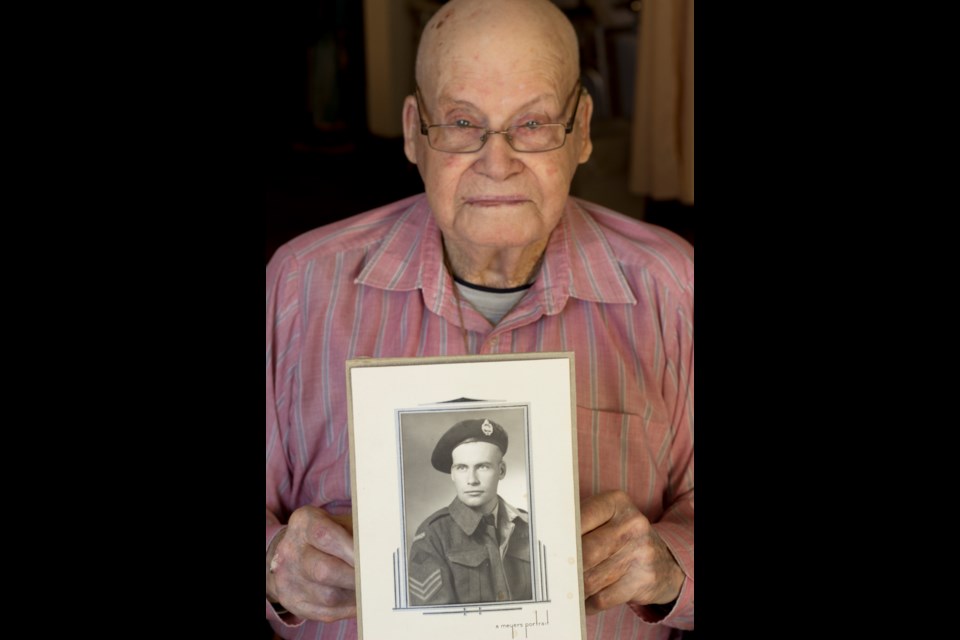

Stewart easily maneuvers himself in his wheelchair in the tight quarters. He proudly shows off his display of black and white photos, medals and momentos he received while serving in World War II. He points out a framed card from Queen Elizabeth II that wishes him a happy 100th birthday. The card, from last month, is the most recent addition to the wall.

As a young soldier Stewart was trained in a town south of Saskatoon. He’s frustrated that he can’t recall the name of the town. His memory isn’t what it used to be, but that was a long time ago. Place names and other trivial details escape his memory. There are some aspects of his time in the service that Stewart can’t forget, even if he tries to.

When Stewart finished rifle training he was offered a position as a sniper. He turned it down and opted to train 19 other rifleman at Boundary Bay Airport. The airport still stands today and is located about 9 kilmetres east of Ladner in Delta, British Columbia. He remembers the wooden posts in the ground that formed a crude border between Canada and the United States. His role was to teach other soldiers how to march and hold their rifles, and to help protect Canada’s border.

It didn’t take long before Stewart joined more than one million Canadians that served in World War II. He can’t recall where he was sent, but he remembers that his job was to be the last one off the boat. Like his comrades he would charge ahead through waist deep ocean water with his rifle over his head.

More than 75 years later Stewart still remembers his most difficult jobs in the service. Stewart recalls returning to a site after a battle and seeing dead men lying face down in the mud. He had to turn over their bodies and remove one of their identification tags. The other tag remained. He would give the tag to a truck driver who would retrieve the bodies and place them in the back of his truck. The driver and Stewart became friends as they were regularly paired up for the gruesome task.

“He was a friend of mine. He went haywire after a while. He got sick of seeing dead people,” Stewart said of the driver.

At night Stewart would sleep on the ground or anywhere where he and his fellow soldiers would be safe from enemy fire. He admits to still feeling “sour” at some comrades who didn’t “do as they were supposed to do” or failed to obey orders.

“You’ve got a job to do, do it,” he said.

“If you haven’t got the guts, you shouldn’t be there.”

After the war, Stewart married his love and bought a quarter section of land near his hometown of Lacadena, Saskatchewan. His father bought a quarter of land beside him and together they raised cows and grew potatoes. His hometown was named after “big water” by a nearby Indigenous group. Often a body of water would melt in the spring and flood his land.

He came to Cochrane after visiting a man who broke horses. The man drove a Ford Model T. He returned once more and fell in love with the foothills and nearby Rocky Mountains. His wife and him built a house near the Bow River.

Charlie Veilleux’s story is different than Stewart's story. Well, every soldier has a different story. Veilleux, 94, was trained and ready to fight for his country. As he waited for his call to go overseas, the war ended.

Veilleux, who also resides at Bethany Cochrane, grew up in southwest Calgary near the historic Lougheed House. His foray into the Navy began when he used to drive a truck full of 14-15 year-old boys from Currie Barracks to Chestermere Lake. He was tasked with teaching the group how to swim. Veilleux couldn’t swim himself.

“They’d all be in the back end of the truck yelling and screaming,” Veilleux chuckled of his trips across the city. He was eventually moved to Toronto to begin training and was stationed on the HMCS Bellechasse allied warship outside Halifax. He tended to the boiler engines by cooling them with water. He was then sent - by train - to Victoria. Veilleux remembers the gruelling five-day train ride across the country. His future sister-in-law Betty - who worked in the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service (Wrens) - followed him around the country.

One day Veilleux and a fellow sailor were walking around Prince Rupert, B.C. when he heard someone calling his name. It was Betty.

“Wherever I went, she followed me,” he said.

One of Veilleux’s jobs in the Navy on the west coast was to shovel coal and ensure the coal burners were filled every four hours at the Wrens living quarters. One day he heard a racket in the coal bin and discovered a very dirty rat. Unsure of what to do he whacked the animal with a shovel rendering it unconscious. He then quickly hurled the animal into the burner.

“He got cremated. That was the end of that rat,” he said.

Veilleux married Betty’s sister Patricia (nee Joyce) on June 23, 1945. They went on to have five children and remained in Calgary. The couple moved to Bethany Cochrane to be near their son Timothy and his wife Lisa. Patricia passed away on October 17, 2018.

Veilleux now spends his days entertaining family and other visitors. He’s never too far from his arm chair that faces his bird feeder and a seasonal flower garden. He keeps a hammer on his window sill and when a pesky black squirrel raids the bird feeder - that he fills every second day - he’s ready to scare it away by tapping the sill.