Once in a while an intricate part of our local history is brought to our attention, making us stand in disbelief of the circumstances involved, just shaking our heads.

Archive papers on this story were presented at the 1997 Canadian Cowboy Conference at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary.

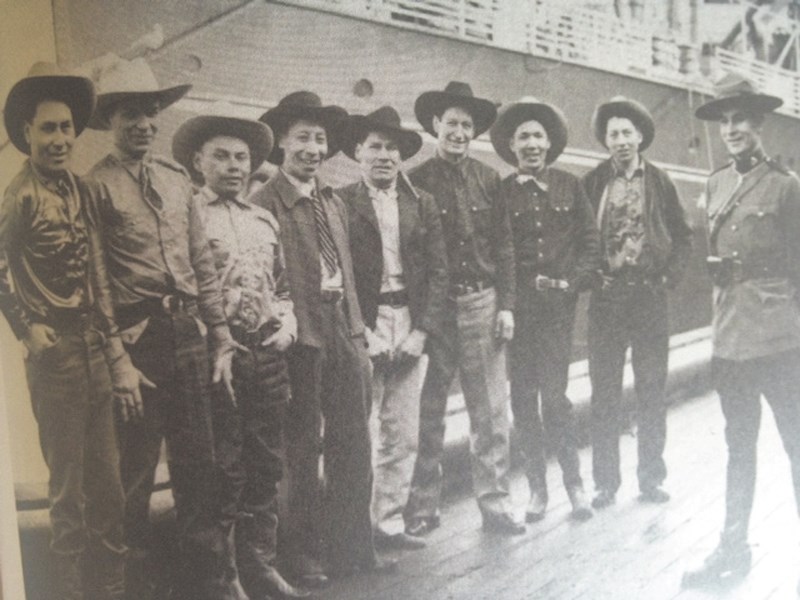

This courageous story is of eight brave, young First Nation men from southern Alberta, who were expert rodeo cowboys. They defied all the odds and managed to obtain permission to compete at Sydney’s Royal Agriculture Society of New South Wales Rodeo in Australia in 1939.

Two of these men, Douglas Kootenay and John Lefthand were from Morley. The other six were Frank Many Fingers and Joe Young Pine from the Blood reserve, Edward One Spot and Jim Starlight from Tsuu T’ina, Joe Crowfoot and Joe Bear Robe from Siksika. They were accompanied by Corporal S. J. Leach from the RCMP.

‘Permission’ in those days was not easily attained. The Indian Act prevented basic freedoms and travel outside the country. Approval had to be obtained from Indian agents; the secretary of Indian Affairs in Ottawa, the minister of Mines and Resources and the inspector of Indian Affairs.

Officials at these levels of government (as well as locally) were against performances in stampedes and exhibitions outside of the country, even after receiving an invitation from other countries. The Indian Act was amended in 1914 to even include punishment if an Indian (as Native Canadians were referred to at that time) chose to participate in any show or exhibition, performance, stampede or pageant in aboriginal costume, without the consent of the superintendent general of Indian Affairs or his agent. Later the words ‘aboriginal costume’ were deleted, but the law stayed in effect until 1951.

Dr. W.B. Murray, who was the Indian agent in Morley at the time, was strongly opposed to this trip, while also trying to discourage rodeos in the community.

The people in Morley had started their own stampede in the 1930s, which he also disapproved of. Apparently, he thought it was too much of a diversion. He simply told the delegates from Australia that ‘rough and risky’ rodeo events were not encouraged, but he didn’t mind the ‘colourful pageantry idea’.

Many negotiations took place over a period of months, leaving a long paper trail, but finally these young cowboys were allowed to sail to Australia.

This historic trip received an abundance of press coverage; however the entire story about the restrictions placed on them by government policies were not disclosed to the public. One editorial comment from a newspaper was, “the Indian cowboys created a sensation in the land Down Under.”

Another Alberta paper wrote that they would set a bad example for young people who might want to “spend every available minute practicing their riding, roping and racing.”

One more editorial comment was, “Now that eight of the top ranking Indian rodeo stars have won themselves a trip half way around the world, it will be still more difficult to convince the embryo braves that their time should be spent in learning to write, read, build a shed or guide a plough.”

They were met by the mayor of Sydney and were well received in Australia; over a million people came to see them perform. However, they were not treated as only cowboys. They had to stay in a teepee village, dress in traditional costume for parades and reluctantly refuse additional invitations to perform in other regions of Australia and New Zealand.

Eddie One Spot was quoted as saying, “From the questions constantly asked, visitors at the exhibition appeared astonished that we were not savages. They were surprised that we all spoke English and were educated, and took an interest in the same things that they did.”

The biggest disappointment for the aboriginal competitors was that they had a different set of competition rules for rodeo events: horseback riding had to be done on English riding saddles; their teams for chuck wagon races were not equal to the competitors’ outfits; and management did not let them compete with the American and Canadian cowboys.

All this did not discourage these young lads. They did far better than anyone expected in most events, verified by bringing home five trophies and several individual prizes. They viewed the entire experience as an opportunity of a lifetime and enjoyed getting to know other indigenous people who taught them how to throw a boomerang and took them on kangaroo hunts.

On the way home they were able to stop in New Zealand, Fiji and Honolulu.

They were fascinated with the different type of archery and fishing spears used in Fiji and even brought some bows home with them.

Influential southern Alberta non-Aboriginal people disapproved of this trip and believed that the eight cowboys were not good role models for young people, which often reduced opportunities for residents of Indian communities.

Our hats go off to our Indian cowboys of 1939, who possessed the spirit of adventure, the courage and the skills to beat all odds.